Roger Bushell’s Last Letter from Stalag Luft III

28-2-44

My Darlings-The mail continues to be appalling and this month’s crop has only produced one letter from Father 30/11/43 + one from Eliza in her own inimitable type writing + dated Nov 11th. Whenever I get one of Eliza’s letters a wave of sympathy for that unfortunate type-writer sweeps over me. What a pounding it must get! The Herculean force which has superimposed an e over a recalcitrant l or z that has got into the wrong place must shake its wretched bones like dice in a box. As for the dashing vertical dashes which constitute the polite fiction of erasure, they are a dagger’s wounds that send the word “to heaven or to hell” far more effectively than did ever Macbeth’s send Duncan. And then there are the complicated mental gymnastics, (which have a charm all their own) required to decypher both the punctuation + the syntax. I start by taking a mental cold plunge into the middle of it, come up gasping, jump out + then wade in with deep breathing exercises from the beginning. Brushing aside obscenities in the text, I dash through, get the general sense (sic) of the thing + then start over again. Next installment next month! Bless you all. I am very well and full of confidence as usual! Roger.

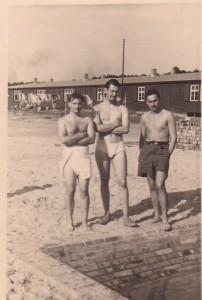

Roger Bushell’s Friend – Tom Kirby Green

Tom Kirby Green (center), with 2 Czech POWs, at Stalag Luft III, circa 1943. Copyright 2014 by John Carr, all rights reserved.

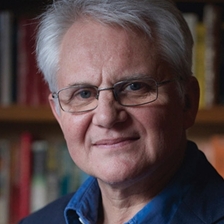

Roger Bushell’s Friend – Bob Vanderstok

Photograph above of Bob Vanderstok, #18 out of ‘Harry,’courtesy of Ben Van Drogenbroek.

Photograph of Vanderstok’s forged ID card from ‘The Great Escape,’ courtesy of Ben Van Drogenbroek.

Comments

Roger Joyce Bushell Speech, Churchill War Rooms, London 15 October 2013

By: The Right Honorable Simon Pearson

Ladies and Gentlemen:

Thank you for joining me tonight in this historic place, a place that is central to my story …. the story of Roger Bushell, the man who led the Great Escape from Stalag Luft III in March 1944.

Three months after the breakout -in June of that year, here – in this place – a memo written by Winston Churchill was circulated and discussed – it may even have been dictated and typed in these rooms. The memo referred to the escape by Royal Air Force officers from Stalag Luft III, the Luftwaffe’s top security camp near the town of Sagan in south-east Germany on the night of March 24.

Seventy-six men had got out of the camp through a 300ft tunnel – 30ft deep and 300ft long – called ‘Harry’.

Three of those men reached England; 23 were captured and returned to Stalag Luft III or other places of internment – and 50 were shot dead by the Gestapo – on the orders of Adolf Hitler. Among them was Roger Bushell.

The British Prime Minister made three points in his memo dated 20 June, as his Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, prepared to address Parliament about the murders of the British airmen.

The first point was: We shall do all in our power to ascertain those who had been responsible for this deed; and to collect evidence on this point;

The second: That no pains would be spared to bring to justice after the war those concerned; And the third: That it would be right in the statement to emphasise the enormity of the act.

Indeed, it was one of the greatest war crimes committed by Nazi Germany against British servicemen. Eden addressed Parliament on 23 June, making a powerful statement that embraced Churchill’s demands. The Foreign Secretary dismissed German explanations that the men had been shot while resisting arrest.He told Parliament:

“His Majesty’s Government must, therefore, record their solemn protest against these cold-blooded acts of butchery … They will never cease in their efforts to collect the evidence to identify all those responsible.

They are firmly resolved that these foul criminals shall be tracked down to the last man wherever they may take refuge. When the war is over, they will be brought to exemplary justice.”

The British kept their word – and virtually all the Germans who took part in the murders were hunted down, including Emile Schulz, the man who shot Roger Bushell.

These were the last acts in a secret war waged by captured RAF officers on the ground in Occupied Europe with the help of British Intelligence, namely MI9 – Military Intelligence 9 – and whose involvement is clearly documented in the National Archive at Kew.

One of the men who prosecuted this war with greatest vigour was Bushell – Squadron Leader Roger Joyce Bushell – sometimes referred to as Big X.

The story of the Great Escape is a remarkable story, familiar, I am sure, to some of you here – an apparently unequal struggle between unarmed prisoners and Hitler’s security forces – a story that resonates with most British men and women whose natural affinity lies with the underdog in almost any struggle.

The story was made famous by the Australian journalist Paul Brickhill, who had been a prisoner in Stalag Luft III, in his book, The Great Escape, but it gained global recognition through the Hollywood film of the same name … indeed, the music from the Hollywood version of the story resonates through British popular culture … and just a few notes from the opening bars strikes a chord with many of us.

But there is more to the Great Escape than the digging of three tunnels – albeit highly sophisticated tunnels – and the struggle was not always quite as unequal as it sometimes appears – thanks in part to the efforts of this remarkable man.

Nor is it a story just about men … primarily the 600 airmen from many nations who had served with the Royal Air Force; who had then been taken prisoner but volunteered to work on Bushell’s escape project in the North Compound of Stalag Luft III.

The Great Escape is also a love story involving a war hero – a flawed hero perhaps – whose achievements have been largely overlooked.

Roger Bushell was a man of many parts … born in South Africa to British parents, he was educated at Wellington College, studied law at Pembroke College, Cambridge, and became a barrister, an international skier, linguist, Spitfire pilot – and, to all intents and purposes, a spy.

Dashing, daring, he loved a prank and always chased excitement – he was a man who knew how to make a party go!!

This is his story, a story of tragedy …the story of 50 murdered men and a doomed romance …but also of great achievements, perhaps even triumph.

Almost exactly fifty years ago, I sat with my father, who had served with the RAF, in a cinema in the Midlands and watched a film that gave a dramatic account of events in the forest south of Sagan, the site of Stalag Luft III.

As with many boys of my generation, the Hollywood epic, The Great Escape, left an indelible mark …

A year or so later, I found Paul Brickhill’s book among my Christmas presents. Perhaps it was not surprising that in a house where bookshelves were lined with the biographies of airmen, and bombers and fighters made from Airfix kits hung from ceilings, I should be interested in this story, but my curiosity about events at Stalag Luft III remained with me and, if anything, became more intense.

My hobby became a quest.

My wife, Fiona, would say it became an obsession – and that I told her all about Roger Bushell on our first date. Indeed, she believes there have been two men in her marriage for the past 20 years!

When the King’s Cup flying competition was held at Tollerton aerodrome near Nottingham, where my father flew at weekends, I met former RAF pilots who had known Bushell. My father took me to Biggin Hill, the fighter base where Bushell had been stationed at the start of the war.

I read many books, but none of them told me much more than Brickhill had done years earlier.

The truth was that, in one of the war stories most cherished by the British, the man at the centre of events was largely forgotten. While the main characters in two of Brickhill’s most popular books – Wing Commander Guy Gibson, who led the Dambusters, and Douglas Bader, the disabled fighter ace – became national icons, Roger Bushell, the hero of a third, faded away.

He did not make the transition from paperback to celluloid in the same manner as Gibson or Bader in British-made films. Hollywood chose composite characters and composite storylines for The Great Escape rather than real people and Bushell – played by Richard Attenborough in the film – became Roger Bartlett. In dozens of books, Bushell appeared in cameo roles, but no one told the story of his life. Why was this? Who was Roger Bushell?

Years later, while working at The Times, I came across a memorial notice in the archive, which marked the anniversary of Bushell’s birth and celebrated his life.

It quoted Rupert Brooke:

“He leaves a white unbroken glory, a gathered radiance, a width, a shining peace under the night.”

It was signed, “Georgie”.

At that moment, I realised there was a love story to be told as well as awar story and that each might inform the other. A friend at The Times, the author Ben Macintyre, told me to stop dabbling: the time had come to write the book.

Within a few hours, I had written to the Imperial War Museum, outlining what I wanted to do and asking for help …

In one of those remarkable twists of fate that can define the outcome of any endeavour, the museum’s response thrust open the door to the story of Roger Bushell’s life.

His family was, at that moment, corresponding with the museum, with the intention of donating his archive. The museum would be happy to pass on a letter from me … it was the start of almost two years of collaboration.

Roger Bushell was a great romantic – he was a powerful man, not quite six foot, with a thick mop of dark brown hair, a strong deep voice and striking, bright blue eyes that seemed to shine in the dark – who was loved by women.

…. but romance was an Achilles’ heel that would torment him through four years of captivity in Nazi-occupied Europe.

None more perhaps than his romance with Lady Georgiana Mary Curzon, a relationship that grew in passion in intensity during 1935… and ignited the fury of Lady Georgiana’s father, Earl Howe, who made a fateful decision that would have tragic consequences for them all.

Photographs taken by Georgie, a beautiful debutante and model, suggest that the affair started in 1934, and letters written later confirm it was both romantic and serious.Pages of a photograph album show a joyous affair: a couple onthe beach, picnicking, and in each other’s arms. One in particularshows a couple sitting on a lawn against a backdrop of trees and bushes, Georgie’s left arm hanging almost protectively around Bushell’s shoulder, the two of them smiling gently, at ease in each other’s company.

In late July, 1935, Bushell accompanied Georgie to the marriage of her brother, Edward, and the heiress Priscilla Weighall, in the chapel of St Michael and St George in St Paul’s Cathedral. Perhaps, just for a moment, Bushell allowed himself to dream of his own wedding in equally grand surroundings.

But Earl Howe was having none of it: Bushell had come too close, and he was not going to allow “that penniless, South African barrister” to marry his daughter.

Earl Howe’s intervention was decisive. Lady Georgiana distanced herself from the man she loved and married a friend of the family later that year. Bushell was left to concentrate on his career as a barrister – “a fledgeling to watch,” wrote the Empire News – and his role as a part-time pilot with 601 (County of London) Squadron, an Auxiliary Air Force unit known as “the Millionaires” due to their ostentatious wealth.

But it would not be the end of the affair with Georgie. She was one of three women who would play a significant role in his tumultuous war.

The Bushell family archive, which contains a collection of letters, his mother’s diary, newspaper cuttings and photographs, provides a partial – and often fragmented – record of Bushell’s life, but it yields three substantial veins of information.

The first is the diary of Bushell’s early life, written by his mother, Dorothe, which sets out the extraordinary close relationship between mother and son. It is an important document, and chronicles the development of a man who clearly needed a woman’s love at every point of his life.

In 1912, at the age of two, Roger made his first trip to England. Dorothe wrote of their journey at sea:

“By now Roger could run at such speed that his old Mummie could not cope with him, and the stewards spent much of the time chasing him down corridors and returning him to our cabin. When possible the steward would carry him round the deck and then into the bar where he received an uproarious welcome …

“Then and there,” she wrote, “I think Roger decided that a bar was a friendly place!””

The second vein of information comes in the form of the many letters Bushell wrote to his family during the four years he spent as a prisoner of the Germans.

A handful of these provide insights into his state of mind at critical periods of the war. Others mask his true intentions, but display the wit of a Cambridge graduate even in adversity.

On 30 November, 1940, when he was a prisoner at the Luftwaffe transit camp known as Dulag Luft near Frankfurt, Bushell wrote:

“My dearest father, your information and lecture about my bill from your tailor was particularly refreshing reading! Tell the old boy he can jolly well extend me credit until after the war. I imagine that your remark – ‘It was at least a friendly action to give you of all people so much credit’ – referred obviously to the fact that I was in a somewhat hazardous job and was no reflection on my financial standing! You will be delighted to hear that in this place I am living well within my income!”

He finished the letter:

“My darlings my page is coming to an end and there is just about room enough left to tell you all how much I love you and how much I think of you.”

“Do you remember how I told you at the beginning of the war that I knew I would get through it. Well admittedly I never thought it would be this way but I am convinced now that there is some destiny which shapes our ends and that all my energies bottled up for the time being are meant to be used later on. God bless you, Roger.”

Portentious words indeed!

A third strand of information – often in the form of clarification – is provided by his father, Ben Bushell, who made notes in the margins of the archive, added after the war as he tried to make sense of his son’s life.

Among the many facts I discovered was that the man who engineered the escape through a 340ft tunnel named Harry was claustrophobic. Roger Bushell hated tunnels. He feared enclosed spaces, even though he grew up on a South African gold mine, and avoided the London Tube whenever possible.

As a child, he enjoyed enormous freedom on the family estate and was, from a very early age, an independent thinker.

According to her diary, Dorothe had one great concern when the Bushell’s sent their son to preparatory school in Johannesburg – and that was his almost absurd devotion to a small teddy bear that he had been given on his fourth birthday. Roger insisted on taking the bear with him to school in spite of Dorothe’s fears that he would be bullied because of it. If there was any trouble, he said, he would fight the boy who caused it.

This happened on more than one occasion, but in the end he was left in peace. Teddy slept with him every night, and, eventually, the bear was looked on as the dormitory mascot.

In January 1924, just as Adolf Hitler was making his first bid for power, Bushell was sent to Wellington College in England, where he excelled at languages and sport. He became the school’s first First Class Scout. Four years later, Bushell’s final school report attributed his popularity to his “indomitable spirit”.

By the age of 18, he was a powerful man, yearning to embrace a high-octane life.

After studying law at Pembroke College, Cambridge, he skied for Great Britain, joined legal chambers in Lincoln’s Inn – and fell in love with Georgiana Curzon, his beautiful debutante.

But Georgie was not the only girl to turn Bushell’s head.

By the late 1930s, some years after his thwarted romance with Georgie, Bushell was having an affair with a woman called Peggy Hamilton, a cabaret girl from the Dorchester who partied with the “Millionaires” of 601 Squadron.

601 was an Auxiliary Air Force squadron of part-time officers, which included Roger Bushell, who was relatively poor by comparison with his peers.

But by this time, Bushell was also making a name for himself.

On weekdays he was distinguishing himself as a lawyer.

His methods of cross-examination were as “unconventional as his slalom technique “, according to Arnold Lunn, the skiing pioneer.

In the years running up to the Second World War, Bushell’s cases made headlines in the national newspapers on many occasions as he defended and prosecuted murderers, thieves and rapists. One trial that caught the public imagination was the case of “The Kissing Café”, in which the owner was accused of profiteering from waitresses who were offering clients something a little more exciting than sugar for their tea and coffee, and charging five shillings rather than the usual sixpence!

Bushell’s friend, Michael Peacock, defended the café owner and Roger the two waitresses, whose behaviour had been witnessed by two undercover policemen.

The Daily Mail reported on Bushell’s cross-examination of the policemen:

“You, Detective Spink,” Bushell said, “with your remarkable hearing, heard cuddling. How do you hear cuddling?”

“When two persons have their arms round each other they make most peculiar noises,” the police officer responded.

“Was this a smacking kiss?” asked Bushell.

“It was a very good kiss.”

“An affectionate kiss that rang out across the room?” inquired Bushell.

“I could not say that,” said Spink.

Bushell was also making a name for himself at weekends with No 601 and, in 1938, he was chosen to fly with the national aerobatics team for the Empire Day air display at Hendon.

His first “combat” of the war was not as a pilot, but as a lawyer, defending two pilots involved in a friendly fire incident in the first hours of the war in which a British aircraft was shot down and its pilot killed.

Bushell helped to win the case – known as the Battle of Barking Creek – in his first telling contribution to the war effort: the courts martial exposed weaknesses in British radar that were corrected in time for the Battle of Britain.

Shortly afterwards, he was promoted to Squadron Leader and given command of 92 Squadron, which had been disbanded after the First World War, at Tangmere in Sussex. The 92 Squadron logbook records his arrival:

“Bushell was posted to command the squadron with effect from 10 October 1939. This officer came from No 601 Fighter Squadron Auxiliary Air Force and is the first AAF officer to be posted to command and form a new squadron ….”

The logbook continued: “The commanding officer was tonight very hospitably entertained at Tangmere Cottage by Lord and Lady Willoughby de Broke and other members of No 65 Squadron and retired to his bed at a late hour, feeling that Tangmere was the best station to be found in the best country in the best of all possible wars!”

He imbued No 92 Squadron with an aggressive fighting spirit – it would become the most successful squadron in Fighter Command, destroying more than three hundred enemy aircraft during the course of the war … but Bushell, leading his unit against overwhelming odds, was shot down on his second mission – on the afternoon of his first day of combat …May 23, 1940 – covering the retreating Allied armies, over northern France.

The squadron logbook records the events of the day:

“The whole squadron left at dawn for Hornchurch where they commenced patrol flying over the French coast. At about 8.30 hours they ran into six Messerchmitts and a dogfight ensued. The result was a great victory for 92 Squadron and all six German machines – Me 109s – were brought down with only one loss to us. It is with great regret that we lost Pilot Officer P.A. G. Learmond in this fight. He was seen to come down in flames over Dunkirk.

In the afternoon, the squadron went out again on patrol and this time encountered at least 40 Messerschmitts flying in close formation. The result of this fight was that another 17 German machines – Me 110s – were brought down – and also 92 Squadron Leader R.J. Bushell – the commanding officer – and Flying Officer J. Gillies and Sergeant Pilot P. Klipsch. Flight Lieutenant C.P. Green was wounded in the leg ….

The remainder of the squadron returned to Hornchurch badly shot up with seven Spitfires unserviceable.

It has been a glorious day for the squadron, with 23 German machines brought down, but the loss of the commanding officer and the three others has been a very severe blow to us all, and to the squadron which was created and trained last October by our late squadron leader.”

The late squadron leader though was very much alive.

Stanley Vincent, the station commander at Bushell’s home base, RAF Northolt, wrote to Bushell’s parents several weeks later:

“It is with the very greatest pleasure that I write to offer our hearty congratulations upon the splendid news that your son is a prisoner of war and not, as we had come to think inevitable, killed in action …”

“We have no details,” wrote Vincent. “So we hope most sincerely that he has not been wounded, and that he is well, and making such a nuisance of himself to the Hun that they will deeply regret having taken him prisoner.”

Bushell was, indeed, doing just that.

At Dulag Luft, he played a key role in engineering the first mass escape of the war.

But he had another role. He was head of military intelligence, which involved the development of coded exchanges with British intelligence through the prisoners’ letters home.

According to the official history of Dulag Luft, which can be found in the National Archive at Kew:

Bushell devoted “himself mainly to acquiring escape intelligence and equipment. But he also dealt with military intelligence, all military information was passed to 90120 S/Ldr Bushell, RAF, who collected it and passed it to the Senior British Officer, who decided what messages were to be sent to IS9.”

IS9 was part of MI9 – an arm of the intelligence services founded in December 1939 with the aim of helping prisoners to escape and encouraging the gathering of intelligence.

While the Germans might have told prisoners that, “For you the war is over,” Norman Crockatt, the head of MI9 had a different opinion.

“Once a fighting man – always a fighting man”.

Contrary to received wisdom, the British did not play according to the rules.

The founding of MI9 on 23 December 1939 with a brief to encourage prisoners-of-war to gather intelligence was a signal that Britain was prepared to breach the Geneva Convention – the rules of war agreed in the 1920s – in its pursuit of victory over the Nazis.

Just days after it was founded, MI9 started briefing officers about its aims – and among its first targets were the pilots of Fighter Command – who it was felt were likely to be among the first men to be taken prisoner.

Among its tasks, MI9 established a number of secret codes that could be used to communicate with London.

Bushell was registered with MI9 in 1940.

At Dulag Luft, the Senior British Officer, Harry “Wings” Day, decided that the gathering of intelligence should be given priority over escaping. His right-hand man was Roger Bushell. The prisoners alerted London to the interrogation techniques being used by the Germans and passed on the codes to other camps.

The Z Report, which documents the development of intelligence activity by British prisoners of war, says: “In late 1940 it became apparent to the Senior British Officer [at Dulag Luft] that the methods of communication with England should be developed from matters regarding escaping to those of military intelligence which it was considered as being of greater importance. From then on a system was developed which would allow the greatest use to be made of any military information which came into the camp, and through the use of coded letters could be despatched to England …”

It was the start of serious resistance to the Germans from among the increasing number of RAF prisoners in Germany – and it would grow in intensity.

Bushell had less success in his love life – and his letters are full of angst in regard to Peggy Hamilton, who had agreed to marry him during the winter of 1939-40.

In a letter to his parents on 27 February, 1941, Bushell wrote: “I still have not heard from Peggy. My last letter from her was dated October 25th … there must be some explanation and I’ll have to be patient I suppose.”

Peggy would not wait for Roger Bushell – but it would be more than a year before he discovered that the cabaret girl from the Dorchester – to whom he had assigned his wartime pay – had married into the nobility and become Lady Marguerite Wentworth Petre.

In June 1941, Bushell escaped from Dulag Luft, hiding in a goat shed on the sports field –

According to one report, a mock bullfight between the goat and the prisoners drew the guards’ eyes as it was meant to, and Roger crawled into the shed. There had been a lot of debate as to how he would get on in the shed. Jimmy Buckley started the old gag by saying: “What about the smell? And Paddy Byrne gave the stock reply. “Oh the goat won’t mind that.”

And as it happened the goat didn’t mind at all!

Bushell, who spoke fluent German, took an express train south and came within 100 yards of the Swiss border before he was recaptured apparently posing as a drunken Swiss ski instructor.

The following night 18 prisoners escaped through the tunnel Bushell had helped to plan and helped to dig in spite of his claustrophobia.

Hitler was informed.

From this moment, the conflict in most RAF prison camps would mirror the war in the air, with both sides seeking technological advantages and more effective intelligence with which to combat the other side in an ever more challenging environment.

The third woman to feature in this story was a Czech resistance fighter called Blazena Zeithammelova, who gave him shelter – and a bed – in Prague after his second escape from German captivity in 1941.

He broke out of a prison train while being moved between camps and – with a Czech airman called Jaroslav Zafouk – headed for Prague.

Bushell arrived in Prague just as “Hitler’s Hangman”, the SS chief Reinhard Heydrich, author of the Holocaust, took over the running of the country with orders to stamp out Czech resistance.

Indeed, Heydrich turned Bohemia and Moravia into an SS state.

Bushell and Zafouk lived with the Zeithammel family – the father Otto, his son Otokar and his daughter, Blazena, who were old friends of Zafouk – but they also worked for the small Czech resistance movement.

They were members of a group run by a man called Josef Masin, known as one of “the Three Kings” of the Czech resistance who specialised in communications with London.

We know that Bushell was at large in the city for several months. We know that he had Czech papers and that he stayed with other Czech families, including the Pridals. We also know that he had an affair with 27-year-old Blazena Zeithammel.

Bushell had rarely shown restraint.

While with 601 Squadron, a senior officer is reported to have quipped: The trouble with Bushell is he’s always hiding a light under himself.”

Bushell was in the Czech capital as British-trained agents planned the assassination of Heydrich – and the Germans later suspected his involvement in the plot. They may have been right.

We do not have proof, just one reference on a Czech website to the young Otokar Zeithammel helping the agents sent from Britain. If the Zeithammels were involved, Bushell would probably have helped too. It is a tantalising prospect in researching this story … but no more than that.

Betrayed by Blazena’s former lover, Bushell was arrested by the Gestapo just before the attack on Heydrich. He was taken to Berlin and interrogated for three months before the Luftwaffe secured his release. Blazena and her immediate family were shot.

The Gestapo papers on the execution still exist and it is possible to piece together the tragic conclusion to Bushell’s life as a fugitive in Prague.

“Several miles from the centre of Prague, high in the northern suburbs, not far from the place where Heydrich had been attacked, is a windswept place called Kobylisy. Amid the lime trees, oaks and maples, perhaps less prevalent in 1942 than they are today, is the Kobylisy firing range, which was established as a training ground for the Austro-Hungarian Army between 1889 and 1891. The Nazis used it for executions.

Here, on a summer’s evening – between seven and eight o’clock on Tuesday, 30 June – after weeks of interrogation and torture, Blazena Zeithammelova was shot. She stood next to her brother, Otokar, who was next to Vojtech Pridal and his wife Ludmilla. Blaza’s father, Otto, stood a couple of places further away. Sigmund Neudorfer, who had supplied Bushell with papers, was there too.

The Gestapo report on the executions, compiled by an officer called Jetrinke from the Police Regiment of Bohemia, said that the sixty-two men and nine women had all been sentenced to death by the Prague court, sitting at Pankrac prison. Jetrinke said the firing squad was drawn from the 2nd Reserve Police Battalion. All those condemned to death were calm and composed before the executions were carried out.

Death was instantaneous in all cases and certified by Dr Stettner. The corpses were put in coffins and taken by lorry to the crematorium where, under police supervision, they were cremated.

Among the Czech patriots who died with the Zeithammels that evening was Josef Masin, on of “the Three Kings”, who had been arrested several months earlier, and other members of his group. Just before he was killed, Masin committed one last act of defiance, standing to attention and shouting: “Long live the Czechoslovak Republic!”

It probably gave them all a sense of courage, perhaps even, as they faced their executioners, a belief that their sacrifices would not be in vain.”

Roger Bushell had come face to face with the reality of Nazi tyranny – And it changed him.

From the moment he arrived at Stalag Luft III, he was determined to wage war on the Nazis.

Escaping was no longer a game if indeed it ever had been.

At Stalag Luft III, he led an international brigade of prisoners who became one of the most belligerent, imaginative and mischievous “armies” ever to confront Hitler’s tyranny.

As “Big X”, the man at the head of the escape committee, he told his fellow prisoners: “The only reason that God allowed us this extra ration of life – and remember, they had all baled out from 25,000 feet or crash landed in blazing aircraft – “is to make life hell for the Hun,” said Bushell.

He organised the digging of three big tunnels known as Tom, Dick and Harry. Tom was discovered when it was almost 300 feet long and ready use.

But the prisoners soldiered on, hiding nearly one hundred and fifty tons of yellow sand that might have given away the existence of a tunnel, and mounting a rigorous security operation organised by Bushell.

In the end, Harry, which was dug from under a stove in Hut 104, became the longest tunnel ever dug in a prisoner of war camp.It was lined with wood, lit by electric bulbs, ventilated through a pumping system, while a railway ran from one end to the other.

At a German courts martial after the escape, the legal officers complained. How an earth could the camp authorities have allowed the prisoners to steal so much public property?

A list included:

1,699 blankets;

192 bed covers;

161 pillow cases;

165 sheets;

3,424 towels;

655 palliases;

1,212 bolsters;

34 single chairs;

10 single tables;

52 tables for two men;

76 benches;

90 double beds;

246 water cans;

1,219 knives;

582 forks;

478 spoons;

69 lamps;

And 30 shovels.

One can’t help but feel that the court had a point.

The prisoners were not entirely reliant on their own endeavours. They found some Germans who were anti-Nazi and prepared to help them. Others Germans were bribed and compromised.

MI9 also weighed in. Using parcels sent by bogus charities – such as the British Local Ladies Comfort Society, the London Jigsaw Club and the Lancashire Penny Fund – it smuggled maps, compasses, radio parts, brushes and inks, and other useful material into the camp – always skilfully hidden.

While escape became the principal industry, Bushell had other targets.

With Wing Commander Harry “Wings” Day, he co-ordinated and expanded the intelligence operation that communicated with London through the coded letters and, among other things, provided the Allies with information about the development of Germany’s secret weapons.

Stalag Luft III became an operational outpost of British intelligence working in breach of the Geneva Convention.

According to the “Top Secret” Z Report on intelligence operations in the RAF camps, the prisoners relayed information on …

1) German secret weapons …

2) Military targets

3) Troop dispositions

4) And industrial data …..

The camp was also the scene of his renewed affair with Georgiana Curzon – conducted through “passionate” letters.

While Georgie’s father, Earl Howe – equerry to King George V – had forbidden them to marry in 1935, events did not turn out as he might have hoped. Georgie’s marriage to Home Kidston, the son of a renowned racing driver, collapsed after her husband had an affair with her own stepmother, betraying both her father and herself, which provoked a scandalous court case in 1942.

In the same year, when Georgie started writing to Bushell, the Gestapo had warned him that he would be shot if he ever found himself in their hands again. But Bushell was a maverick who challenged authority all his life – and he was determined to get home to Georgie in spite of pleas from fellow officers that he remain behind.

After the mass escape in March, 1944, when 76 Allied officers broke out of the camp, Hitler demanded the execution of at least 50 of them. Bushell was probably at the top of the list of condemned men.

Bushell, accompanied by a young Frenchman, Bernard Scheidhauer, travelled further and faster than any of the other prisoners, reaching Saarbrucken on the French border within 24 hours.

There, just as in the Hollywood film, a German security officer, checking their papers, made a quip in English – and one of the two men replied in English. It was probably Bushell, the man who had briefed all the other prisoners on how to deal with the German security forces.

They were handed over to the Gestapo and shot on the motorway outside Kaiserslautern on March 29.

Georgiana refused to accept Roger’s death until some years afterwards when she placed the first of her memorial notices in The Times. It read:

“BUSHELL, Roger J., Squadron Leader, RAF, 92 Squadron. On this his birthday and always in proud treasured memory of my beloved Roger, who was murdered by the Gestapo in March, 1944, after escaping from Stalag Luft III.

‘And if I grieve, as lonely hearts do grieve,

I am less loyal to you, who were my sun

And moon and stars. Oh, brave and valiant one,

Have you not left me this proud legacy? –

Courage to face the future without you,

And patience to endure the loneliness,

In sure and certain faith we meet again.

Where there is no more sorrow – neither tears.’”

The notice ended, “Love is immortal”, and was signed “Georgie”.

Bushell’s father, Ben, composing the epitaph for his son’s gravestone in Poznan, Poland, had perhaps, the last word. He wrote:

“A leader of men,

He achieved much,

Loved England,

And served her to the end.”

The Killing Field, August 2005

Photograph Courtesy of Dr. Silvano Wueschner

Google Maps Coordinates Kindsbacher Straße 49, 66877 Ramstein-Miesenbach, Germany

This is the field where Squadron Leader Roger Bushel died.

Here, near the west gate of the Ramstein Air Base, is where Nazi officers dropped him to his knees in the final seconds of his life.

It has taken me over two years to get here.

Two years of dreaming this man back to life, and searching for the people who might remember him. Two years to learn that with his knees driven into the same earth I am standing upon now, he turned just before the pistol was fired, to get a last glimpse of his executioner. To glare at him. To show his contempt. To renounce his own fear.

I don’t sleep anymore.

I am haunted by this man.

And by that image of him turning at the moment he did, so that the Gestapo agent standing behind him in his long coat, the agent called Dr. Spann, was forced to shoot him in the back. The shot echoed off a church steeple and a ridge of hills that stretched across the horizon as Roger rolled onto his side, drew his knees to his stomach and groaned as he glanced back once again before the second bullet exploded through in his skull.

Here, near Kaiserslautern, Germany, by the side of the road that morning on March 29, 1944, in the last moments, the brightness dimmed from Roger’ Bushell’s blue eyes as his murderer put a lie to all that he had dreamed of being in this world and to the greatness he was so certain was at hand for him.

This place marks the end of his life and the beginning of being forgotten. I know that now. I am both angry and mystified by it.

I stood here at dusk as the cars raced past. Their fabulously engineered engines humming with a certain arrogance that bothered me. I was already disappointed that the place where Bushell perished was marked, not by a monument but by a public toilet of stainless steel and polished concrete. And by yellowed sheets of newspaper caught in the branches of sickly pine trees; by beer bottles at my feet, beneath the ugly, low steel railing that marked the edge of the highway. There was no marker of a man’s death or life or of his struggle in the end. No scent in the air of the Seine River and the warming fields of France forty kilometers to the west of here where Roger was dreaming of that morning—The safe house there where he would lay low for a few days, a week or maybe a few months, before he found his way back to a fighter squadron and resumed waging war against the German bastards who sought to enslave England. There was nothing in this place that recalled the remarkable journey that had brought him here, or his story.

Or of the people who inhabited his story: The family in South Africa who grieved for him. His dear friend who would become the prosecutor in the Nazi war trials at Nuremburg to try to get even in some way for what they did to Roger. The woman in England who pledged herself to him and then stopped waiting for him to return from the War. Or the other woman. The woman in Czechoslovakia who made love to him in the fifth story flat on Stefanikovna Boulevard, just before she turned him over to the Nazis; Roger careful not to pass before the tall windows of that building with so many people milling about in the city streets below as he took her in his arms. Not because he loved her but because she had promised him a way out of captivity and back into the fight. Into the war again.

What could she have known of this man? He would have told her nothing, on the run as he was, an RAF pilot shot down over Dunkirk, a POW escaped from a German prison camp, recaptured and locked in cattle car on a freight train crossing Germany when he sawed through the wooden planks of the floor then dropped below onto the rails to be free again.

She knew nothing of this. He was a stranger to her. His past as unknown as his future. For taking him into her arms, into her bed, into her life, she would be killed by the Gestapo. But not before she unwittingly set into motion one of the great examples of human achievement.

Here is the mystery of life, the puzzling nature of human existence. That what seems to be random and haphazard turns out to be something else entirely. It turns out to be Fate. Or call it Destiny. That a lonely platinum blonde in a cheap dress entices a stranger to take her clothes off and to make love to her. And then, because he won’t profess his undying loyalty only to her, because he can’t love her and take her with him, she betrays him. She hands him over to his enemies for thirty pieces of silver, thereby making possible one of the astonishing enterprises in history. Years later, long after she is dead, it will be called The Great Escape. The story of how 600 prisoners of war in a German camp secretly dug one hundred and thirty tons of earth to build a tunnel thirty feet deep and three hundred and fifty five feet long. How they worked night and day for a year and a half, building a railway in that tunnel, and intricate radio receivers, and perfectly detailed passports forged with stunning precision, and two hundred functioning compasses, and a tailored suit of clothing for each man. Including this one man who pulled her stockings to her ankles and made love to her in her father’s bed in her father’s house.

Because he was already an escaped prisoner when she took him in her embrace, the Nazis shot her up against a wall and took their money back, depriving her of ever learning that this man was the mastermind behind it all. That this man who engineered the Great Escape would come to redefine for men at war the meaning of courage and defiance.

It had taken me a long time to get here from Chicago, from my life where I am an attorney. My life, hectic and passing too quickly just like yours. I have always been a most reasonable man, plodding along through my responsibilities with my head down, not prone to obsessions or exaggerated ideas. I had struggled for almost two years to fit my research of Roger’s story into the small spaces of my ordinary life. A week’s vacation spent in Cape Town. Another in Poland. A long car drive to Quebec to the place where Roger skied as a Cambridge undergraduate. I searched for him everywhere, taking my small steps forward, and then falling back, wondering where all of this would lead in the end. What I would know of this man, Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, when I finally came to the end, was that I knew him better than any other person I had ever known.

There was frustration at almost every turn. Even finding this place in Germany had been difficult. I had taken three wrong turns off the A6 Autoban before I found the right place, the place that matched the artist’s sketch. In my coat pocket, I had the sketches by the Royal Air Force Special Investigation Branch Team, and the transcript pages from the Nazi war crimes trials that convicted Bushell’s executioners. Two pages that identified the exact place where he was shot. Now I felt strangely like I had been here before, and was returning after a long absence.

My mind turned to another place, to another field.

Returning. To a field in Zagan, Poland where I had stood in March 2004. In the empty forest where the tunnel emerged on the far side of the barbed wire fence surrounding Stalig Luft III. A famous place. It was winter. The trees were stripped bare. The ground was still frozen. Dead branches snapped beneath my foot steps. I walked through the forest on March 24, at eleven pm, exactly the time the first men had emerged from the tunnel that night in 1944. I had wanted to be there at that exact moment, to try to feel what Bushell might have felt. I retraced the route from the tunnel to the railroad station half a mile north of the camp. The BBC was there to mark the 60th anniversary of The Great Escape. I met a few of the men from the prison camp. And one survivor of the escape, Jimmy James, who had spent two years there. He didn’t know much about Bushell, which surprised me. Two men living in a prison camp for two years, building a tunnel together, a tunnel that could just as easily have turned out to be their graves. But no one knew Bushell. He had walled himself off from everyone in that camp, which was not his nature to do. But in the prison camp he had been appointed by the senior British officer to organize and execute this escape plan, and so he was alone at the top. In his civilian life he had been a barrister, but here he was the judge and jury. He alone decided if a man had the strength of will, the courage, the patience, to be in on this secret escape plan. He made enemies here in this field. He left some men behind. Men he decided were not up to the requirements the escape. Of his dream.

I am back in Germany now.

One of the men Roger had chosen, died here in this field with him.

Bernard.

I took the transcript pages from my pocket again and held them to the light. The stick figure sketch that could have been drawn by a six year old child has the title: DESCRIPTION AS BREITHAUPT SAW THE TWO VICTIMS AND THE GUNMEN. KRIMINAL SEKRETAR SCHULZ ON THE LEFT. THEN BUSHELL AND BERNARD (IDENTIFIED AS ENGLISH PILOTS) THEN DR. SPANN.

A short distance away, were the Gestapo car and the driver, Breithaupt, who would be the witness.

I read the transcript pages again, word for word again, in the fading light of dusk. This is Schulz speaking, Schulz who would in time be hanged for his part: “I put the handcuffs on the rear seat of the car, took my pistol out of its holster and walked around the back of the car. At that moment I heard shots fired and Dr. Spann shouting, but I could not tell what he was shouting. I saw both officers falling to the ground and I then fired a single shot at the taller of the officers. I could not be sure if my shot hit, but the two officers fell forward to the ground. The smaller one fell face downwards, and the taller one fell sideways and dropped on his right side and slowly turned over on his back. He drew up his legs and made a groaning sound, and I could see that he was in great pain. He did not speak, and I lay down on the grass close to him, and taking careful aim, I shot him through the left side of the head.”

I folded the pages and turned towards the highway where a single car caught my attention. One car racing past all the others. Distinguishing itself in the heavy traffic. I smiled. That would be Roger, driving faster than the rest of them. Insisting on being out in front. Roaring through the last light of the day. More than anything, he loved speed and despised moving slowly. At age 3 he took his mother’s car for a spin. During his years at Cambridge he had raced his MG through the streets of London, that car he loved, a disgraceful little hardtop that had cost him ten pounds British Sterling. The petrol attendants shaking their heads. He loved that. And then in the south of England learning how to fly Tiger Moths out over the Cliffs of Dover. Those flimsy bi-planes that appeared to be held together by strings and canvas. He pushed them harder than they were meant to be pushed. I stood on that field too, the old grass runway at Duxford air base in England. I saw the rolling hills and the ancient stone walls and the enormous hangers large enough to hold a zeppelin. The place where Roger trained to fly., and where the townspeople sent their children out of the room each time Roger began cursing on the wireless. The grounds crews shaking their heads. Muttering his name after every hair raising landing. Bushell.

And here in this field, another name beside his. Bernard. Bernard Scheidhauer, a French pilot, who had dug the tunnel with Roger. And ended up here. He was one of those selected by Bushell. One of those who was not content to sit out the remainder of the war in the German camp where the Nazis placated their prisoners with a camp newspaper, and golf clubs, a library and an ice hockey rink. It was a peculiar sort of confinement meant to drain the fight out of a man. To Roger this was an abomination. Sitting there day after day while his friends died in war. All his life he had believed that his destiny was for greatness. Greatness of some kind. He knew it was out there just ahead of him, and when the war broke out he grew certain that he had been born at the right time and was meant for something heroic in this war. And now he was sitting in a camp theatre run by the enemy watching his comrades perform Gilbert and Sullivan, airmen, men he knew in drag playing the female roles. This was a denial of his destiny. An abomination that drove him to the edge. And the only solace was the tunnel. The Great Escape.

So, Bernard had followed him to this field rather than stay behind and live out the war in a prison camp where the cigarettes were not that great and the ice on the hockey rink was never quite right, but you were safe, and you would make it home in the end to the people who were waiting for you.

Instead he died for following Roger Bushell, who was following his destiny. Instead he became one of the 76 men who escaped that night, emerging from the end of the tunnel beyond the barbed wire fence and then making their separate ways across Europe.

Roger’s plan had been to get 200 out; his mad vision had been to empty the camp in the dead of night so that when the Germans awoke everyone would be gone. That would be greatness!

But it didn’t come to pass. The tunnel, it turned out, was twenty feet short, so that when the first man stuck his head up from under ground, he was in an open field illuminated by spot lights rather than at the edge of the forest where Roger promised they would be. His plan failed that night. A mathematical error Roger should not have made forced over a hundred men, already dressed in their escape clothing and dreaming of the world beyond the prison camp, to remain behind.

They were the lucky ones, it turned out.

Two months after September 11, I began the process to join the Army. I felt like it was the right thing to do. At officer’s training in Fort Lee Virginia we ran through the Civil War battlefield at Petersberg, Virginia, past the crater that marks the tunnel built by Pennsylvania coal miners from General Grant’s army. Another tunnel. Another war. During those weeks, I told no one of this book that had begun to take over my imagination and my life. I thought of Bushell. I had his letters with me, the letters he had written home during the war, and he was on my mind. But I didn’t speak of him, or of my intentions because I was still confused by something. Why had Roger Bushell been forgotten? In the hundreds of books written about the Great Escape, there was barely a mention of him, the man who organized and dreamed it into existence. In the damned Hollywood movie, “the ultimate Tinkertoy sandbox movie,” that became an icon of pop culture, no mention of him. No handsome movie star to play his role. Roger’s father said it best, when he saw Roger’s character on the screen: “Mind you, the fellow in the film is no more like my son than an old boot.”

Why had Bushell disappeared across the years since the Great Escape? There at Fort Lee I tried to answer the question. But it wasn’t clear to me until the end of the day in the field where he was killed. I knew it then. Not to be remembered is one thing. To be forgotten is something else. And the mystery of this, how he could have been forgotten, was part of the story that had its claws in me. A forgotten soldier dead on the side of the road, like so many now in the television images from Iraq and Afghanistan. Soldiers who had followed someone there to the side of the road, like Bernard had followed Roger to this ugly place. This worthless strip of land. As Roger lay dying here he would have known that he was responsible for Bernard dying beside him. His vision of greatness, his belief in destiny, were to blame for this. As Roger lay dying he may have wondered if the others who escaped with him would meet the same end. If somehow the brilliant vision he had for his life brought destruction to all those men who had believed in him. Of the 76 men who escaped from the tunnel, all but three were rounded up within a few weeks. Fifty were executed by the Nazis. The truth lies in these numbers. In truth then, Roger Bushell’s Great Escape was an exquisite failure. And forgetting him had been intentional.

Why was it intentional? Because forgetting, to those who loved and knew him, was a shield against the poison drops of crippling sorrow. Because forgetting, to the bureaucrats in the RAF, was easier than awarding him a medal. Roger Bushell never received a wartime decoration for his valiant service.

I knew this suddenly, the way you know certain things. And that made me even more determined to resurrect him, and to tell this story of his life.

Written in 2007, with notes I had taken along this stretch of the A6 in 2005.

John Carr